-

Navigating Existence in the Digital Millennium 21 November, 2024

-

How to Study Philosophy? 03 October, 2024

-

How to Write a Philosophy Paper? 03 October, 2024

-

Why Study Philosophy 27 September, 2024

-

How to Learn Philosophy 27 September, 2024

-

Philosophy of Artificial Consciousness: Can Machines Ever Truly Think? 20 September, 2024

About

Our conference covers topical philosophical issues of modern society and the development of the philosophy of science and technology, legal and socio-cultural issues of states, issues of spiritual and physical health of nations. The conference will be attended not only by teachers and scholars, but also by representatives of other countries.

Opportunity to talk to leading philosophers

The conference offers a unique opportunity to meet and network with recognized experts in the field of philosophy. You can ask them questions, discuss your ideas, and get valuable feedback and advice from seasoned professionals.

Expanding your professional network

The conference provides an excellent opportunity to establish new professional contacts. You can meet colleagues from different countries and institutions, discuss joint research projects with them, exchange contacts, and expand your professional network.

Intellectually stimulating and inspiring

The conference provides a unique atmosphere where you are surrounded by like-minded people who are passionate about philosophy. You'll engage in stimulating discussions, listen to interesting speeches, and get exposed to new ideas. This will help you broaden your thinking, gain new insights, and be inspired to explore further.

The Philosophy Conference is a unique opportunity to share your research, ideas, and passion for philosophy with an international community of scholars and practitioners.

Conference program

First Day

09.30-10.00 - Registration of conference participants. 10.00-10:30 - Opening of the conference. Welcome speech of the organizers

Second Day

09.30-10.00 - Introductory remarks by the speakers. Planning for the day. 10.00-10:30 - Presentation "Prospects for the existence of humanity: philosophical and cultural aspect"

The organizers and keynote speakers

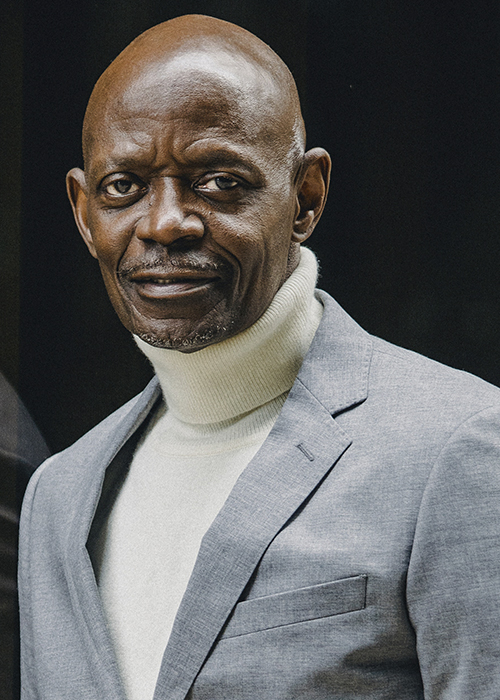

Robert Boykin

Professor, Doctor of Philosophy

Deborah Balfour

Associate Professor of Philosophy

John Reddish

D. in Philosophy

Eunice Harland

D. in Philosophy, Lecturer of the Department

Our Blog

frequently asked questions

The aim of the conference is to bring together leading philosophers and scholars to exchange ideas, present new research and theories, and hold discussions and debates on philosophical topics. The conference promotes philosophy and the exchange of knowledge in the field.

The conference will present a variety of topics covering a wide range of philosophical issues. These may include studies in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, political philosophy, philosophy of science, philosophy of art, and other philosophical fields.

The conference will present a variety of topics covering a wide range of philosophical issues. These may include studies in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, political philosophy, philosophy of science, philosophy of art, and other philosophical fields.

The conference can use a variety of formats, including plenary sessions, parallel sessions, roundtables, panel discussions, and poster opportunities. This provides attendees with a variety of opportunities to network, exchange ideas, and engage in active discussions.

The conference can provide opportunities for networking and sharing through formats such as cocktails, coffee breaks, lunches, and evening events. Attendees can meet, network with peers, ask questions and receive feedback from other conference participants. This creates a positive atmosphere for making new professional contacts and exchanging ideas with like-minded people.

The conference may offer opportunities for publication and dissemination of research through the conference proceedings, which may be available electronically or in print format. This allows participants to disseminate their research and receive feedback from the scientific community. It is also possible to participate in breakout sessions or panel discussions where research can be discussed and further developed.

The Ethics of Chance: A Philosophical Examination of Gambling

Ancient Wisdom in Modern Times: Relevance of Greek Philosophy

Navigating Existence in the Digital Millennium

Amplifying Ideas, Muting Noise: The Role of Acoustics in Philosophical Conferences

How to Study Philosophy?

How to Write a Philosophy Paper?

Why Study Philosophy

How to Learn Philosophy

Philosophy of Artificial Consciousness: Can Machines Ever Truly Think?

Stoicism and Modern Mental Health: Ancient Wisdom for Contemporary Challenges

The Ethics of Chance: A Philosophical Examination of Gambling

Ancient Wisdom in Modern Times: Relevance of Greek Philosophy

Navigating Existence in the Digital Millennium

Amplifying Ideas, Muting Noise: The Role of Acoustics in Philosophical Conferences

How to Study Philosophy?

Partnerships Proud To Be a Part Of

Rainbow Riches is a well-liked slot game that features an Irish theme and vibrant visuals. With its assortment of bonus features, including free spins, players can enjoy thrilling gameplay and have the chance to win big.

Fortune favors the bold at Casino Pin Up Peru! Join today and discover a world of exciting games and massive jackpots.

Fortune favors the bold at Casino Pin Up Peru! Join today and discover a world of exciting games and massive jackpots.

Check out the complete list of trusted non Gamstop casinos, made up by Steve Ashwell. Big bonuses, best games and top manufacturers are waiting for you to join.

When it comes to playing for real money, Australian online casinos provide a secure and regulated environment. Licensed operators ensure fair play, using sophisticated Random Number Generators (RNGs) to determine game outcomes. Top-tier security measures protect your personal and financial information, offering peace of mind as you focus on the thrill of the game.

Writing a philosophy essay takes a great understanding of a subject and massive writing skills. In order to be 100% sure it’s a real goal we recommend looking for the best paper writing service, especially if it’s reviewed by A*Help.

Writing a philosophy essay takes a great understanding of a subject and massive writing skills. In order to be 100% sure it’s a real goal we recommend looking for the best paper writing service, especially if it’s reviewed by A*Help.

If you are looking for a professional ghostwriter bachelor thesis, you have come to the right place. We offer high-quality academic writing services that will help you achieve your academic goals.

We have good news, because we are starting to cooperate with Leon Bet Casino with the support of an expert in online casinos from Greece – Aris Kladis (OC24 LTD, GreekOnlineCasinos.com project). We believe that our partnership will lead to qualitative changes.

We are an academic ghostwriting agency looking for qualified master thesis ghostwriters. If you have in-depth knowledge in your field and want to have a master’s thesis written, please contact us.

We have compiled a list of the best Polish online casinos play-fortune.pl/kasyno/legalne-kasyna-online/. All of the casinos on our list are legal and licensed, and they offer a wide variety of games to choose from.

We have compiled a list of the best Polish online casinos play-fortune.pl/kasyno/legalne-kasyna-online/. All of the casinos on our list are legal and licensed, and they offer a wide variety of games to choose from.  Many students turn to online assignment help to enhance their understanding and improve their grades. This service has become increasingly popular as the demands of modern education grow.

Many students turn to online assignment help to enhance their understanding and improve their grades. This service has become increasingly popular as the demands of modern education grow.

If you need assistance with your assignments, we suggest reaching out to the ghostwriting service that has been established since 2007 and is highly trusted by numerous clients. Their team of ghostwriters offers expert support, ensuring top-quality help for all your academic requirements.

If you need assistance with your assignments, we suggest reaching out to the ghostwriting service that has been established since 2007 and is highly trusted by numerous clients. Their team of ghostwriters offers expert support, ensuring top-quality help for all your academic requirements.

Education and development Beep casino

Education and development Beep casino

Streamline your IB success with our IB IA Writing Service. From research to writing, our Internatoinal Baccalaureate professionals are here to guide you through every step of your Internal Assessment writing process.

Streamline your IB success with our IB IA Writing Service. From research to writing, our Internatoinal Baccalaureate professionals are here to guide you through every step of your Internal Assessment writing process.

Discover how the premier soundproofing company in New York can transform your space into a serene oasis. Click to learn more about the top-rated New York soundproofing company that delivers unmatched results!

Stigan Media enhances your criminal law practice’s online visibility through targeted SEO for criminal lawyers, driving the right clients directly to your doorstep.

Stigan Media enhances your criminal law practice’s online visibility through targeted SEO for criminal lawyers, driving the right clients directly to your doorstep.

Fortune Coins is a premier sweepstakes casino available in the U.S. and Canada, offering free-to-play games with exciting chances to win real cash prizes. Join today and enjoy thrilling slots, table games, and more with no purchase necessary!

Fortune Coins is a premier sweepstakes casino available in the U.S. and Canada, offering free-to-play games with exciting chances to win real cash prizes. Join today and enjoy thrilling slots, table games, and more with no purchase necessary!

Looking for Salesforce development services? Explore Innowise, a reliable provider known for its expertise in Salesforce customization and implementation.

Looking for Salesforce development services? Explore Innowise, a reliable provider known for its expertise in Salesforce customization and implementation.